There was a time when the internet felt different—when it wasn’t a maze

of dark patterns designed to manipulate your attention, when software

was built for the user, not for the highest bidder. Back then, a browser

was simply a tool, a window to the world, not a marketplace disguised as

an app.

Somewhere along the way, that changed.

Today, browsers are riddled with engagement traps. They

track you, sell your data, shove crypto schemes in your face, and call

it ‘innovation.’ But real innovation isn’t about bloated AI

assistants or endless monetization tricks. Real innovation makes life

simpler, not more exhausting.

I built Zen because I believe the browser should serve you. It should be

fast, transparent, and private by design—not as a checkbox feature, but

as a philosophy. It should get out of your way, so you can get in, do

what you need to do, and step away from the screen without feeling

drained.

I’m not a corporation. I don’t have a marketing team

crafting sleek slogans, nor a boardroom plotting engagement metrics. I’m

just a developer who saw what was wrong and decided to fix it. Zen isn’t

about gimmicks. It’s about respect—for your time, your privacy, and your

right to a better web.

It won’t be perfect, and I won’t

pretend to have all the answers. But with the help of a passionate

community, I know we can build something that matters. A browser that

doesn’t fight against you, but works with you.

There was a browser that kind of did this, Arc.

For a while, it felt like a breath of fresh air: a browser that

challenged conventions, that cared about design, that aimed to make

browsing feel intentional rather than chaotic. It rethought the

interface, introduced thoughtful features, and for a moment, it seemed

like someone finally got it.

But then, things changed.

The Browser Company, Arc's VC-backed creators, became

ambitious, and they decided that their loyal user-base still fell short

of their goals to compete with the big names like Chrome, right from the

start. Thus, they announced that Arc was "good enough" and went off to

work on a new AI-powered browser.

Yet, it wasn't. The

Windows version was a shadow of what was promised—slow, unstable,

missing core features. The MacOS version was in a better state, but

performance and stability gradually degraded with every update. What

started as a vision for a better browser quickly became yet another

company chasing after monetization, pivoting to AI gimmicks and

engagement loops instead of refining the core experience. Thus, Arc was

finished, before it had even reached its real potential.

I won’t pretend Arc didn’t inspire me. It did. There’s a lot to admire

in its design philosophy, in its willingness to rethink how we interact

with the web. But inspiration isn’t imitation. I’m taking the

good—thoughtful UX, a clean interface, a focus on user control—and

cutting out the bad. No forced online accounts. No feature bloat

disguised as innovation. No chasing trends just to stay relevant.

Zen

isn’t about maximizing engagement. It’s about minimizing friction. It’s

about building a browser that works with you, not on you. And beyond

that, I’m exploring my own ideas—rethinking not just how a browser

looks, but how it feels to use. How it fits into your life without

demanding more of your attention than necessary. While it's still in

early development, I'm excited to share it with you, and to hear your

thoughts on how we can make it better together.

So, what's the plan?

Zen is still in its early stages, but it’s growing fast. I’m

working on a roadmap that focuses on the essentials: mantain firefox

updated and secure to gain trust, improve the UI/UX to make it more

intuitive and enjoyable, and implement features that make your life

easier, not more complicated.

Arc's Basic Features

Expand on our own interesting ideas

Final touches, polishing and rebrand for stable release

The future of Zen isn’t set in stone. It’s a work in progress, shaped by

your feedback, your ideas, and your needs. I’m not building this browser

for me. I’m building it for you—for all of us who believe the web can be

better, who want to take back control of our digital lives, and who

refuse to settle for the status quo.

If you’re tired of

browsers that treat you like a product, if you’re looking for a

different way to browse, if you believe in a web that respects your

privacy and your time, then I invite you to join me on this journey.

Let’s build something that matters. Let’s build a browser that respects

you.

I also want to invite you to contribute, if you have any ideas,

suggestions or want to help in any way, feel free to let us know. Some

zen features where completely community driven, implemented by external

contributors. We are always looking for new ideas and ways to improve

the browser.

The internet deserves better.

So do you.

~ mr. m ✌️

From customization to clarity: lessons learned building Zen Browser.

TL;DR

I'm not a design expert, just someone learning through building Zen.

These are personal just thoughts. I hope they spark reflection,

especially for those in the FOSS community. Read with an open mind,

think beyond what I’ve written, and if anything resonates or you

disagree, feel free to reach out. I’d love to talk more and keep on

learning!

Don't worry, don't uninstall Zen inmediatedly. This isn’t about

removing all customization. Zen will always support mods and deeper

tweaks for those who want them, just not at the cost of thoughtful,

opinionated design.

Read, reflect, and enjoy! ‹3

A year ago, I set out to build a browser. Not just any browser, but my

browser. One that would reflect my values, my needs, my ideal vision of

the web. I called it Zen Browser.

Like many developers, I started by dreaming big: total customization,

endless tweaks, and fine-grained control over every pixel. But somewhere

along the way, something changed.

What I found instead was clarity, not in complexity, but in simplicity.

In choosing design that respected the user, instead of overwhelming them

with choices.

The Allure of Customization

There’s something exciting about total freedom. Developers love the idea

of giving users endless choice. It feels democratic. Respectful.

Open.

That’s how I started. Zen Browser was going to be fully moldable. You’d

shape it to your needs, down to the smallest detail.

But what I learned is that more choice doesn’t always mean a better

experience. In fact, it often leads to decision fatigue. Users get lost

in the settings instead of enjoying the product. And many never find a

setup they actually love, they just keep tweaking.

At some point, I realized that no one ever said,

“I love this browser because I spent three hours configuring it.”

They just said, “It works. It feels right.”

The Turning Point

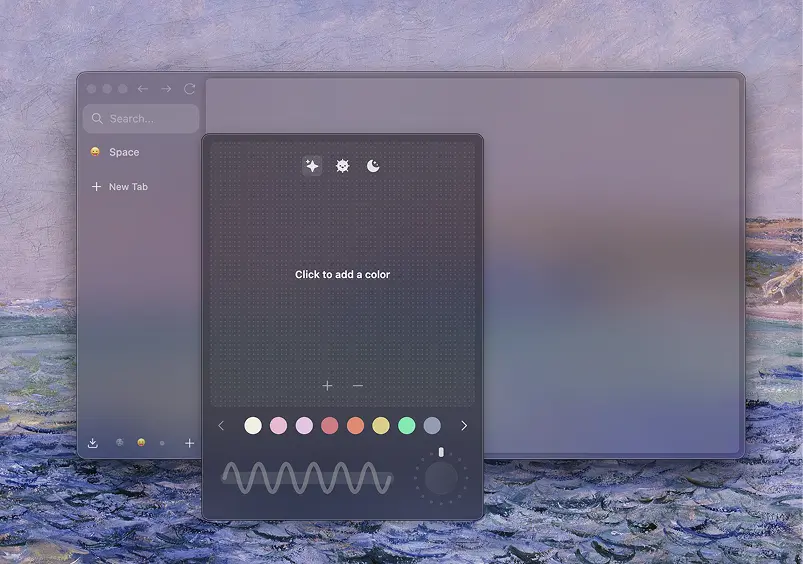

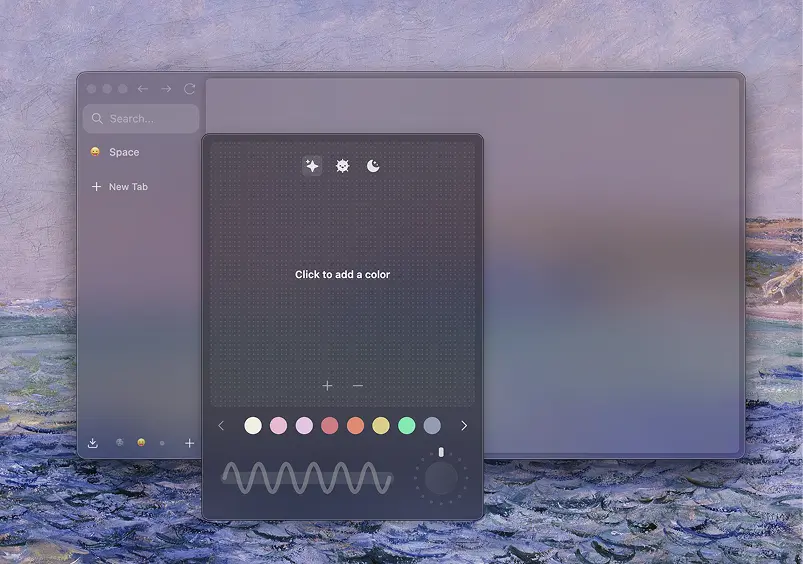

It happened with something as small as a color picker.

Zen Browser's original color picker was incredibly flexible. You could

set any color, rotation, gradient style, it was a playground. Total

freedom. And on paper, it was a win. Users could make their browser look

exactly how they wanted.

But something didn’t sit right. The more I used it, the more I noticed

the results often looked... off. Some color combos clashed. Others

lacked contrast. Gradients looked messy or chaotic. The feature was

powerful, but it didn’t guide anyone. It just gave them tools and walked

away.

That’s when I looked at what Arc did, and I’ll admit, we copied it. (Big shock, I know.)

We removed the rotation. We enforced color harmony. Gradients had to use

complementary or analogous tones. The result? No more wild combinations.

No more chaos. Suddenly, every workspace had colors that just worked.

Gradients that felt designed, not generated.

Not everyone liked the change. People asked why they couldn’t tweak

things the old way. They missed the freedom. But I

didn’t miss it. In fact, I felt proud.

That was my turning point. When I realized I didn’t want to make

something endlessly customizable. I wanted to make something beautiful.

Something that felt finished. Something that didn’t ask to be fixed or

adjusted, it just looked good, because it was designed that way.

That moment, over a simple color picker, defined everything that came

next.

Looking back, it wasn’t just about colors. It was about clarity. I

realized that good design isn’t about offering every option, it’s

about making the right choices so the user doesn’t have to. That shift

changed everything about how I approached Zen.

Finding the Sweet Spot

Total rigidity can be just as limiting as total freedom. The real

challenge, and the real art, is in finding the balance between the

two.

That’s where the idea of sensible defaults, respectful overrides came

in. With Zen, I wanted most users to open the browser and feel like it

was already finished. Clean, quiet, considered. But I also wanted to

leave a door open, discreet, intentional, out of the way, for those who

needed more.

That’s why advanced preferences exist. Hidden settings.

Power-user flags. The kind of features you don’t stumble into, but

deliberately reach for. Like the ability to bring back full gradient

control in the color picker. Or override animation timings. Or adjust

tab behavior beyond the default.

These aren’t features for everyone. They’re escape hatches for those who

know what they want. And keeping them tucked away preserves the core

experience for everyone else.

The sweet spot isn’t compromise. It’s clarity, knowing what your product

stands for, while still leaving space at the edges for people who ask

for more.

What I Learned

This past year didn’t just teach me how to build a browser. It taught me

how to think.

I used to believe that more options made a better product. That users

wanted control above all else. But I’ve learned something deeper, people

don’t open a browser to tweak. They open it to use. And the best

experience is the one that’s already great, before you touch a single

setting.

-

Customization is not a replacement for good design.

If your product only shines when users tweak it, you haven’t

finished it.

-

Defaults matter more than features. Most people never change

settings.

What they see first becomes their entire experience.

-

Good design is opinionated, and that’s okay. You’re

allowed to make decisions on behalf of the user, as long as those

decisions are thoughtful and respectful.

-

Hidden power is better than visible clutter. Give

advanced users what they need, but keep the surface calm and

approachable.

-

Every decision sends a message. Even a toggle

switch tells the user what kind of product they’re dealing with,

precise and focused, or chaotic and unfinished.

Zen Browser got better the moment I stopped trying to please everyone

and started trying to serve someone, someone who wants clarity, not

control. Someone who wants to open their browser and feel calm, not

busy.

A Quiet Conclusion

I’m not a design expert. I didn’t study user experience or typography or

color theory. I’m just someone who built a browser, made a lot of

mistakes, and slowly started to see things differently.

Zen Browser isn’t perfect. It still has rough edges. There are things

I’d change, and things I’m still unsure about. But if there’s one thing

I’ve learned, it’s that

simplicity takes more courage than complexity. It’s

easier to add features than it is to say “this is enough.”

This past year taught me to trust the user, not by handing them the

entire toolbox, but by giving them something they can rely on.

Something that feels considered.

If you're building something of your own, I hope you don’t feel pressure

to make it do everything. Maybe just focus on making it

feel right. Thoughtful defaults. Strong ideas. Gentle

polish. That’s what people remember.

Not the number of settings. Not the sliders or toggles. Just how it made

them feel. That’s the kind of design I’m still learning to do. And I

hope to get better at it, one

release at a time.

So, if you’re building something, remember this:

You don’t have to please everyone. You just have to care deeply about

someone.

Stay safe out there. Build with clarity. And never feel bad for not

pleasing everyone.

~ mr. m ✌️

I've been day-and-night playing around with Arc's color picker in order

to understand how it works, and how I can make it better.

I wanted to share what's the magic behind Zen's color picker, and how it

works behind the scenes because it let me learn a lot about design,

color theory, mathematics, and overall, push myself to learn more about

interesting topics that I never thought I would be interested in!

This blog will be quite long and technical, so I recommend you to

grab a cup of coffee or tea, and sit down to read it. I will try to make

it as interesting as possible, but I can't promise that it will be easy

to read.

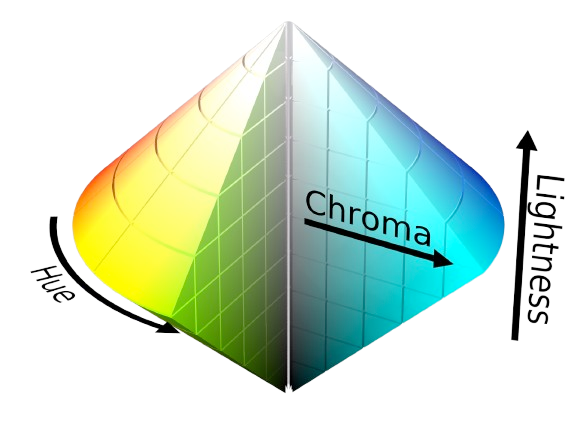

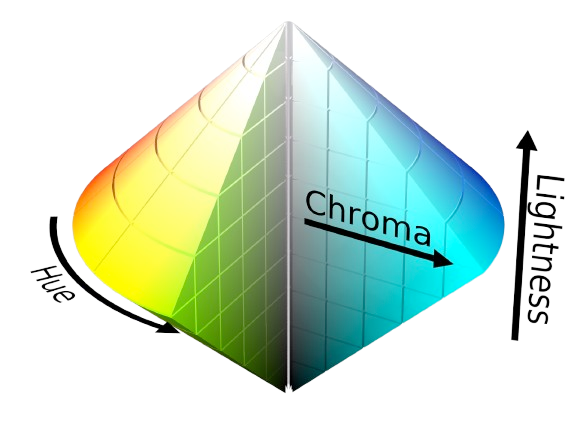

Extracting colors: Part 1 - The HSL color model

Colors are a fascinating topic, and there are many ways to represent

them. The most common way is the RGB color model, which represents

colors as a combination of red, green, and blue. But no, we are not

going to use RGB, we are going to use the HSL color model instead.

HSL is represented as a combination of hue, saturation, and lightness.

Unlike RGB, HSL is formed in a 3D space, making it more interesting to

work with

in a 2D space.

Extracting colors: Part 2 - The HSL color picker

The way colors will be represented in our color picker is by calculating

the position of our dots from the middle of the color picker, to extract

the hue, saturation, and lightness values from the position of the dot.

First, let's start by doing simple calculations around the center of the

color picker, we need to know: the angle from the center to the dot, and

the distance from the center to the dot.

Note: The angle is in degrees, and the distance is in pixels.

Now that we have the distance and angle, we can calculate the hue,

saturation, and lightness values. Please note that the normalized

distance is calculated by subtracting the distance from 1, so that we

get more chromatic colors when the distance is closer to the center, and

more desaturated colors when the distance is closer to the edge of the

color picker.

Displaying colors: Part 1 - Dark mode or light mode?

Now that we have an RGB color after converting the HSL values, we need

to decide whether to use a light or dark mode for the sidebar theme.

This is a very important decision, because since we can go from white to

black in the color picker, we need to decide whether to use a light or

dark mode for the sidebar theme, so that the text is always readable.

The way we do this is by checking the lightness value and deciding what

theme to used based on the contrast from both text colors, and the

background color.

First, we need to calculate the luminance of the background color when

blended with the text color (to simulate text opacity), and then we can

compare the contrast ratios to decide on the theme.

TODO: NOT FINISHED YET

The last few days have been some of the hardest of my life. For the

past 3 days, you had stopped drinking, and every time you managed to

eat something, you would end up vomiting it a day later. I knew

something was wrong, but I kept hoping you would pull through like you

always did.

Then came the call from the vet. The words I never wanted to hear. I

had to make the hardest decision of my life, to say goodbye. My heart

broke in that moment, but I knew it was the right thing for you.

I wanted to take you on one last walk, to feel the breeze and see the

world together one more time. But you couldn't. You made it only about

20 steps outside the house before you just fell on the floor, too weak

to keep going. That was the moment I realized I would never see you

run again, or jump again, or watch your tail swing happily behind you.

The world seemed to stop right then. I sat beside you, holding you,

wishing I could make it all better.

You were my best friend, my family, my comfort through everything.

Thank you for every wag, every cuddle, every happy moment we shared. I

will miss you more than words can ever say.

The next day, the house was so quiet. No soft paws, no gentle

breathing, no tail tapping against the floor. Just silence. It felt

like the world had lost a bit of its warmth without you in it. Every

time I walked into a room, I expected to see you there, looking up at

me with those big, loving eyes. But you weren't. And that hurt more

than I can say.

Rest now, my sweet girl. You'll always be in my heart.

Picture of her last walk, taken just hours before she passed

away.

Picture of her last walk, taken just hours before she passed

away.